Brooklyn… The New Havana?

In a former church, 6 Cuban artists launch a season of residencies

Published: August 01, 2017

Why is the Cuban municipality of Manzanillo producing so many of the island’s strongest young artists? And how did four of them (plus two habaneros) end up in Brooklyn? Elvia Rosa Castro muses on the long-ago difficulties of getting a residency abroad, the pioneering work of the Cuban Artists Fund, and the Cubans who came to Brooklyn this spring.

For the visual arts academy in Trinidad, Cuba, the 1990s were a golden age. The academy regularly won prestigious Académica prizes, and on graduating, many of its students entered ISA, (the Higher Institute of Art), with some of them already deemed promising and worth watching. (The school that managed to feed the most students into ISA—that Parnassus of art education—had the best reputation among students, even if it wasn’t decreed in writing or by any institution.)

Artist conversation at RU with, from left: curator Mary Kate O’Hare, Alejandro Campins, curator Rafael DiazCasas, and José Yaque; Courtesy Residency Unlimited

Several now well-known names emerged from those classrooms: Wilfredo Prieto, Inti Hernández, Jimmy Bonachea, Alexander Guerra, Duvier del Dago (all members of the DUPP group, winners of the Unesco Prize for the Arts in the 2000), plus Ariel Orozco, Jorge López Pardo, Humberto Díaz, and Odey Curbelo. In the timespan from about 1998 to 2003, perhaps the most gifted artist of that generation in terms of prizes, scholarships, and residences was Yoan Capote, who did not come from the center of the island but rather from western Pinar del Río.

By this, I mean to say that access to these prizes and scholarships, from Cuba, was very difficult. Even getting access to the calls for entry was miraculous. Without Internet, and with the painful and distressing adventure of traveling from Cuba before immigration reform (letter of invitation, travel permit, and limited stay abroad), access to these opportunities was more impossible than the Moro Utopia. During that time, Lázaro Saavedra made an illustration for the Pensando alto (“Thinking High”) section of Artecubano magazine, which, in a cynical tone, gave some “tips for getting a scholarship.” Later, when I asked him for advice, he answered ironically: “a friend who informs you about the scholarship”—that is, simply finding out about it. Applying online—having the nerve to write the keywords—was essentially improbable.

We now receive newsletters and regular access to information. For those of us over the age of 33, that is still a bit overwhelming.

Elizabet Cerviño, performance of Contenido neto, 2006; Courtesy elizabetcervino.com

Back then, it could be that an artist would win an award or scholarship and then be unable to take advantage of it, due to the denial of visas to the United States. That happened with some artists who had gotten Guggenheim Fellowships, for example. Trips to the US were unstable and practically impossible, CIFO had not yet set its eyes on Havana in an emphatic way, CINTAS was for Cubans in the diaspora, and the Farber Foundation did not yet exist. The Garaicoa Studio´s project Artist x Artist project is relatively new, and back then, Galería Continua seemed a whisper that would never reach the Cuban capital.

In this scenario—back in 1998—the Cuban Artists Fund emerged in New York. For artists, this organization’s focus was, at the time, the Vermont Studio Center. Several Cuban artists residing on the island have passed through the Center, and still do.

Artist conversation at RU with, from left: Jorge Wellesley, curator Meyken Barreto, curator María de Lourdes Mariño Fernández, and Elizabet Cerviño; Photo: Cuban Art News

Everything seems more normal now (I say it seems because nothing is forever now), and the issue of visas and travel between Cuba and the United States has been fairly standardized. Round trips prophesized by Gerardo Mosquera many years ago are now being fulfilled. Cuba has become fashionable and is now on the radar. In recent years Cuban Artists Found has diversified its collaborations beyond Vermont. The Times Square Alliance and Residency Unlimited have hosted CAF-award-winning Cuban artists in the Big Apple.

Time passes and things change. For various reasons the Trinidad academy fell into a slump and then disappeared from the island’s teaching map. Manzanillo, to the east, whose pupils studied in Holguín, Santiago de Cuba, and in the local academy, took the lead during the first decade of the 21st century.

Look through the catalogue of Bomba, curated by Píter Ortega at the Wifredo Lam Center, and you´ll see I am right. Manzanillo artists, from Yornel Martinez, Michel Pérez, and Alejandro Campins to Luis Enrique López and Elizabet Cerviño, didn’t arrive in Havana with a concept in hand, but with poetry and some existential extravagance.

Yornel Martínez, Pure Land, 2014; Courtesy Residency Unlimited

Of rare sophistication, they brought with them the mystique of the Gulf of Guacanayabo and the Cabo Cruz caves. While everyone tried hard to catch curators’ and collectors´ attention, they entered the scene without hurry or anxiety. (The other fact is that they are good artists, and that’s taken for granted. Several have already been included in the central exhibition of the Havana Biennial, and in the paradigmatic exhibitions of this century. Collectors seek them out.)

When all the opportunities I’ve mentioned finally came together, this group, as a whole, had matured. It’s not surprising, then, that Galeria Continua has set its sights on them, for one thing. And it’s also not surprising that, of the six Cubans who were awarded residencies by the Cuban Artists Fund this spring at Residency Unlimited, four are from Manzanillo: Alejandro Campins (1981), José Eduardo Yaque (1985), Yornel Martínez (1981) and Elizabet Cerviño (1986). Havana’s Reynier Leyva Novo (1983) and Jorge Wellesley (1979) complete the list of Cuban guests in Brooklyn.

Jorge Wellesley during the conversation at RU; Photo: Cuban Art News

The birth dates of these artists tell us they belong to the same generation, and this implies a shared sensibility: a willingness to discredit. For them, “there is no transcendental meaning,” at least not in political-ideological matters. Through painting, installation, video, or books-objects, each of them has sabotaged the traditional narrative (historical, official, identity-based), in some cases from poetic intimacy and in others from caustic, disenchanted commentary. Works like Patria, a series of paintings by Alejandro Campins, Los olores de la guerra (The Scents of War) by Novo, and What inspires us by Wellesley not only illustrate my point but are key works of Cuban art of these times.

Reynier Leyva Novo, Los olores de la guerra (The scents of war), 2009; Courtesy Bildmuseet, Umea

Another element that unites almost all of them is the use of writing in their works: Wittgenstein, found in Yornel and Wellesley, poetry in Elizabet, and the parody of political discourse in Novo. (These four participated in the show I already know to read. Image and text in the Latin American art, Centro Wifredo Lam, 2011). The decentralization of the notion of landscape, close to the minimal and the conceptual, is another shared element.

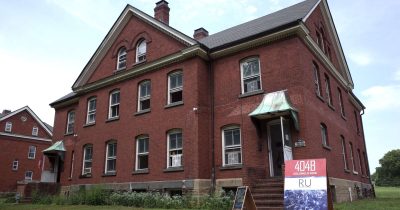

Awarded nonprofit status in 2011, Residency Unlimited “supports the creative process and promotes exchange through its unique residency program and year-round public programs.” A former church functions as its headquarters (as is the tendency in many places) and this already makes it an attractive proposition. Cuban artists were welcomed this spring for the first time, in a program that included exchanges with curators and artists, visits to museums and cultural institutions, presentation of works in the studio, and public conversations with moderators.

Residency Unlimited, Brooklyn; Photo: Andrzej Raszyk

How important is it for RU to invite Cuban artists? Nathalie Anglès, the organization’s director, says that “cultural diversity is key to a successful residency environment,” noting that in 2017, “we have the privilege of hosting residences of artists from diverse regions such as Cuba, Singapore, Russia, Haiti, Nigeria, Macedonia, Albania and Kosovo.”

Nathalie told me that the Cubans have met with a positive reception. “There is a great deal of interest in meeting artists based in Cuba. At the presentations, there were curators from major institutions and who worked independently as well. Some of them already knew their [the artists’] practice but they wanted to meet the artists.”

Reynier Leyva Novo, left, and Yornel Martínez during their artist talk at RU; Courtesy Residency Unlimited

Staying in New York, with a generous program of exchanges of all kinds, is an experience that will surely be revealed in the works of these young people, and for the good. The links, the networks, and the types of exchange generated by these programs allow participating artists to discover areas and contexts of creative work that were previously unexplored, while at the same time having short, medium, and long-term impact on their thought and creation. Programs like these make Cubans equal, and makes us realize that we are not the navel of the world.

2017.jpg)

Reynier Leyva Novo, A Happy Day (Donald Trump), 2017; Courtesy Residency Unlimited

Elvia Rosa Castro (Sancti Spíritus, 1968) has a degree in Philosophy and a Master’s in Art History. She is an art critic, editor, and independent curator. She was awarded the National Prize for Curation and the Guy Pérez Cisneros prize for Criticism. Her most recent book is Los colores del ánimo. She is also the CEO of the blog Señor Corchea.